Memory, History, Forgetting

Paul Ricoeur

Translated by Kathleen Blamey and David Pellauer

LOOKING BACK OVER AN ITINERARY: RECAPITULATION

pp.494-506

Happy Memory

I can say after the fact that the lodestar of the entire phenomenology of memory has been the idea of happy memory. It was concealed in the definition of the cognitive intention of memory as faithful. Faithfulness to the past is not a given, but a wish. Like all wishes, it can be disappointed, even betrayed. The originality of this wish is that it consists not in an action but in a representation taken up again in a series of speech acts constituting the declarative dimension of memory. Like all speech acts, those of declarative memory can also succeed or fail. For this reason, this wish at first is not seen as a vow but as a claim, saddled with an initial aporia, one which I have repeated over and over in the following words: the aporia that is constituted by the present representation of an absent thing marked with the seal of anteriority, of temporal distance. If this aporia has constituted a genuine difficulty for thought, it has never been cast as an impasse. The typology of mnemonic operations was thus from start to finish a typology of the ways in which the dilemma of presence and of absence can be overcome. The royal theme of the recognition of memory was gradually developed on the basis of this arborescent typology. At the start it was simply one of the figures of the typology of memory, and it is only at the end, in the wake of the Bergsonian analysis of the recognition of images and under the fine name of the survival or revival of images, that the preeminence of the phenomenon of recognition was confirmed. Today, I discern in it the equivalent of what was characterized as the incognito of forgiveness in the preceding sections of this epilogue. But only an equivalent, to the extent that guilt is not the discriminating factor here but rather reconciliation, which places its final stamp on the entire series of mnemonic operations. I consider recognition to be the small miracle of memory. And as a miracle, it can also fail to occur. But when it does take place, in thumbing through a photo album, or in the unexpected encounter with a familiar person, or in the silent evocation of a being who is absent or gone forever, the cry escapes: "That is her! That is him!" And the same greeting accompanies step by step, with less lively colors, an event recollected, a know-how retrieved, a state of affairs once again raised to the level of "recognition." Every act of memory (faire-mémoire) is thus summed up in recognition.

The rays extending from this lodestar spread beyond the topology of memory to the whole of the phenomenological investigation.

The reference to happy memory allowed me from the start to put off the contribution of the neural sciences to the knowledge of memory until the end of this book. The underlying argument was that the understanding of mnemonic phenomena takes place in the silence of our organs as long as dysfunctions on the plane of actual behavior and of the conduct of life do not require taking into account the forms of knowledge that have the brain as their object.

It was the same presupposition of self-clarity in the phenomenon of recognition that next supplied the blade that cuts between two types of absence — the anterior and the unreal - and so, as a matter of principle, sunders memory from imagination, despite the disturbing incursions of hallucination into the mnemonic field. I believe that most of the time I can distinguish a memory from a fiction, even though it is as an image that the memory returns. Obviously, I would like always to be capable of making this distinction.

It is still the same gesture of confidence that accompanied the exploration into the uses and abuses that flag the reconquest of memory along the paths of recall. Blocked memory, manipulated memory, commanded memory - so many figures of difficult, but not impossible, recollection. The price to be paid was the conjunction between the work of memory and the work of mourning. But I believe that in certain favorable circumstances, such as the right given by another to remember, or better, the help contributed by others in sharing memories, recollection can be said to be successful and mourning to be checked along the fatal slope of melancholy, that attraction to sorrow. If it were so, happy memory would become memory at peace.

Finally, the reflexive moment of memory culminates in the recognition of oneself in the form of a wish. We resisted the fascination with the appearance of immediacy, certainty, and security likely to be found in this reflexive moment. This too is a vow, a claim, a demand. In this respect, the sketch of a theory of attribution, under the threefold figure of the attribution of memory to the self, to close relations, and to distant others deserves to be reconsidered from the perspective of the dialectic of binding and unbinding proposed by the problematic of forgiveness. In return, by extending in this way to the sphere of memory, this dialectic is able to move out of the sphere specific to guilt to attain the scope of a dialectic of reconciliation. Placed back in the light of the dialectic of binding-unbinding, the self-attribution of the set of memories that compose the fragile identity of a singular life is shown to result from the constant mediation between a moment of distantiation and a moment of appropriation. I have to be able to consider from a distance the stage upon which memories of the past are invited to make an appearance if I am to feel authorized to hold their entire series to be mine, my possession. At the same time, the thesis of the threefold attribution of mnemonic phenomena to the self, to close relations, and to distant others invites us to extend the dialectic of binding-unbinding to those other than oneself. What above was presented as the approbation directed to the manner of being and acting of those I consider to be my close relations - and approbation counts as a criterion of proximity - also consists in unbinding-binding: on the one hand, the consideration addressed to another's dignity - and which was credited above with being an incognito of forgiveness in situations marked by public accusation - constitutes the moment of unbinding stemming from approbation, while sympathy constitutes the moment of binding. It will be up to historical knowledge to pursue this dialectic of unbinding-binding onto the plane of the attribution of memory to all the others beyond myself and my close relations.

In this way the dialectic of unbinding-binding unfolds along the lines of the attribution of recollections to the multiple subjects of memory: happy memory, peaceful memory, reconciled memory, these would be the figures of happiness that our memory wishes for ourselves and for our close relations.

"Who will teach us to decant the joy of memory?" exclaimed André Breton in L'Amour fou, providing a contemporary echo, beyond the Beatitudes of the Gospel, to the apostrophe of the Hebraic psalmist: "Who will make us see happiness?" (Psalm 4:7). Happy memory is one of the responses given to this rhetorical question.

Unhappy History?

Applied to history, the idea of

eschatology is not without equivocalness. Are we not returning to those metaphysical or theological projections that Pomian places under the heading of "chronosophies," in opposition to the chronologies and chronographies of historical science? It must be clearly understood that we are concerned here with the horizon of completion of a historical knowledge aware of its limitations, whose measure we took at the beginning of the third part of this work.

The major fact made apparent by the comparison between history's project of truth and memory's aim of faithfulness is that the small miracle of recognition has no equivalent in history. This gap, which will never be entirely bridged, results from the break — it could be termed epistemological - made by the system of writing imposed on all the historiographical operations. These, we have repeatedly stated, are from start to finish types of writing, from the stage of archives up to literary writing in the form of books and articles offered to reading. In this regard, we were able to reinterpret the myth of the Phaedrus concerning the origin of writing — or at least of the writing entrusted to external signs — as the myth of the origin of historiography in all of its states.

This is not to say that every transition between memory and history has been abolished by this scriptural transposition, as is verified by testimony, that founding act of historical discourse: "I was there! Believe me or not. And if you don't believe me, ask someone else!" Entrusted in this way to another's credibility, testimony transmits to history the energy of declarative memory. But the living word of the witness, transmuted into writing, melts away into the mass of archival documents which belong to a new paradigm, the paradigm of the "clue" which includes traces of all kinds. All documents are not testimonies, as are those of "witnesses in spite of themselves." What is more, the facts considered to have been established are also not all point-like events. Numerous reputedly historical events were never anyone's memories.

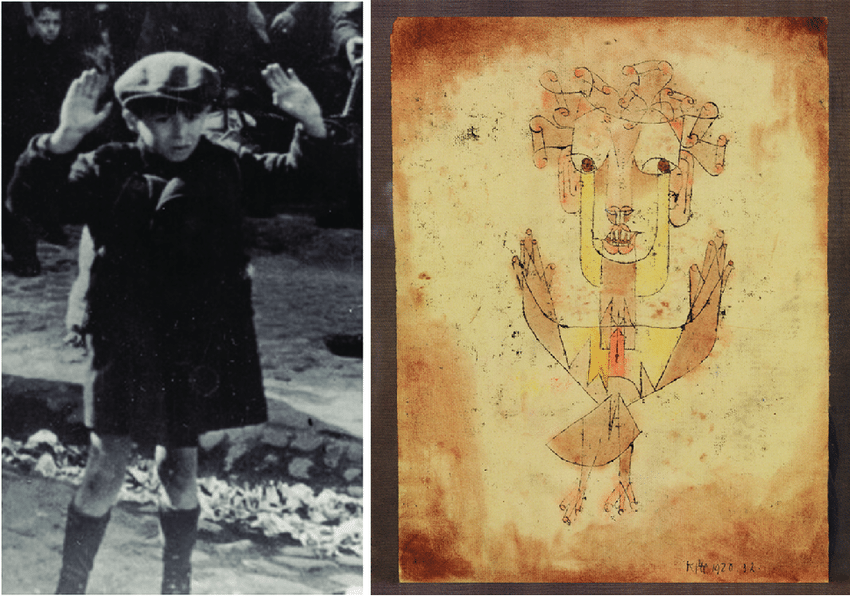

The chasm between history and memory is hollowed out in the explanatory phase, in which the available uses of the connector "because..." are tested. To be sure, the coupling between explanation and understanding, which we have continued to underscore, preserves the continuity with the capacity for decision-making exercised by social agents in situations of indecision and, by this means, the continuity with self-understanding dependent on memory. Historical knowledge, however, gives the advantage to those architectures of meaning that exceed the resources of even collective memory: the articulation between events, structures, and conjunctures; the multiplication of the scales of duration extended to the scales of norms and evaluations; the distribution of the relevant objects of history on multiple planes — economic, political, social, cultural, religious, and so on. History is not only vaster than memory; its time is layered differently. History's greatest distance from memory was reached with the treatment of the facts of memory as "new objects," of the same order as sex, fashion, death. Mnemonic representation, our vehicle of our bond with the past, itself becomes an object of history. The question was even legitimately raised whether memory, the matrix of history, had not itself become a simple object of history. Having arrived at this extreme point of the historiographical reduction of memory, we allowed a protest to be heard, one in which the power of the attestation of memory concerning the past is lodged. History can expand, complete, correct, even refute the testimony of memory regarding the past; it cannot abolish it. Why? Because, it seemed to us, memory remains the guardian of the ultimate dialectic constitutive of the pastness of the past, namely, the relation between the "no longer," which marks its character of being elapsed, abolished, superseded, and the "having-been," which designates its original and, in this sense, indestructible character. That something did actually happen, this is the pre-predicative - and even pre-narrative — belief upon which rest the recognition of the images of the past and oral testimony. In this regard, events like the Holocaust and the great crimes of the twentieth century, situated at the limits of representation, stand in the name of all the events that have left their traumatic imprint on hearts and bodies: they protest that they were and as such they demand being said, recounted, understood. This protestation, which nourishes attestation, is part of belief: it can be contested but not refuted.

Two corollaries result from this fragile constitution of historical knowledge.

On the one hand, mnemonic representation, lacking the assurance of recognition, has as its sole historical counterpart the concept of standing for, whose precarious nature we have underscored. Only the work of revising and of rewriting engaged in by the historian in his workshop is capable of reinforcing the merit of the presumption that the constructions of the historian can be reconstructions of events that actually occurred.

Second corollary: the competition between memory and history, between the faithfulness of the one and the truth of the other, cannot be resolved on the epistemological plane. In this respect, the suspicion instilled by the myth of the Phaedrus is the pharmakon of writing a poison or a remedy? — has never been dispelled on the gnoseological plane. It is reawakened in Nietzsche's attacks against the abuses of historical culture. A final echo resounded in the testimonies of some prominent historians regarding the "uncanniness of history." The debate must then be transferred to another arena, that of the reader of history, which is also that of the educated citizen. It is up to the recipients of the historical text to determine, for themselves and on the plane of public discussion, the balance between history and memory.

Is this the final word on the shadow that the spirit of forgiveness would cast on this history of the historians? The true response to the absence in history of an equivalent to the mnemonic phenomenon of recognition can be read in the pages devoted to death in history. History, we said then, has the responsibility for the dead of the past, whose heirs we are. The historical operation in its entirety can then be considered an act of sepulcher. Not a place, a cemetery, a simple depository of bones, but an act of repeated entombment. This scriptural sepulcher extends the work of memory and the work of mourning on the plane of history. The work of mourning definitively separates the past from the present and makes way for the future. The work of memory would have attained its aim if the reconstruction of the past were to succeed in giving rise to a sort of resurrection of the past. Must we leave to the avowed or unavowed emulators of Michelet alone the responsibility for this romantic wish? Is it not the ambition of every historian to uncover, behind the death mask, the face of those who formerly existed, who acted and suffered, and who were keeping the promises they left unfulfilled? This would be the most deeply hidden wish of historical knowledge. But its continually deferred realization no longer belongs to those who write history; it is in the hands of those who make history.

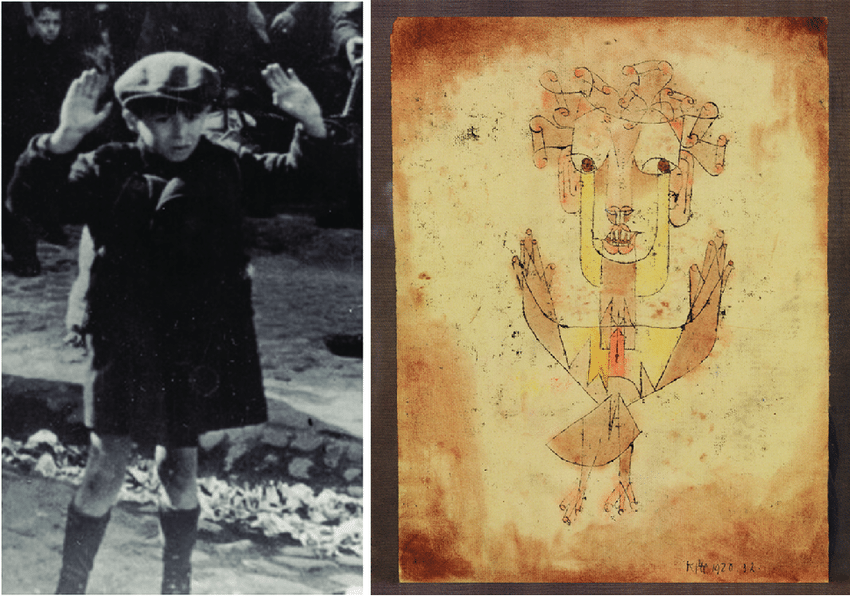

How could we fail to mention here Klee's figure titled Angelus Novus, as it was described by Walter Benjamin in the ninth of his "Theses on the Philosophy of History" "A Klee painting named Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling up wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress". What, then, is for us this storm that so paralyzes the angel of history? Is it not, under the figure of progress which is contested today, the history that human beings make and that comes crashing into the history that historians write? But then the presumed meaning of history is no longer dependent on the latter but on the citizen who responds to the events of the past. For the professional historian there remains, short of that receding horizon, the uncanniness of history, the unending competition between memory's vow of faithfulness and the search for truth in history.

Should we now speak of unhappy history? I do not know. But I will not say: unfortunate history. Indeed, there is a privilege that cannot be refused to history; it consists not only in expanding collective memory beyond any actual memory but in correcting, criticizing, even refuting the memory of a determined community, when it folds back upon itself and encloses itself within its own sufferings to the point of rendering itself blind and deaf to the suffering of other communities. It is along the path of critical history that memory encounters the sense of justice. What would a happy memory be that was not also an equitable memory?

Forgiveness and Forgetting

Should we confess in fine something like a wish for a happy forgetting? I want to express some of my reservations regarding assigning a "happy ending" to our entire enterprise.

My hesitations begin on the plane of the surface manifestations of forgetting and extend to its deep constitution, on the level where the forgetting due to effacement and the reserve of forgetting intertwine.

The ruses of forgetting are still easy to unmask on the plane where the institutions of forgetting, the paradigm of which is amnesty, provide grist to the abuses of forgetting, counterparts to the abuses of memory. The case of the amnesty of Athens, which concerned us in the final chapter on forgetting, is exemplary in this regard. We saw how the establishment of civil peace was based upon the strategy of the denial of founding violence. The decree, accredited by oath, ordering that "the evils not be recalled" claims to do no less than to hide the reality of stasis, of the civil war, the city approving only external war. The body politic is declared to be foreign to conflict in its very being. The question is then posed: is a sensible politics possible without something like a censure of memory? Political prose begins where vengeance ceases, if history is not to remain locked up within the deadly oscillation between eternal hatred and forgetful memory. A society cannot be continually angry with itself. Then, only poetry preserves the force of unforgetting concealed in the affliction that Aeschylus declares "lust of power insatiate" (Eumenides, v. 976). Poetry knows that the political rests on forgetting the unforgettable, "that never formulated oxymoron," says Nicole Loraux (La Cité divisée, 161). The oath can evoke and articulate it only in the form of the negation of the negation, which decrees the non-arrival of this misfortune, which Electra proclaims to be itself a "sorrow, which... cannot be done away with, cannot forget" (Electra, v. 1246-47). Such are the spiritual stakes of amnesty: silencing the non-forgetting of memory. This is why the Greek politician is in need of the religious figure to uphold the will to forget the unforgettable, under the form of imprecations verging on false oaths. Lacking the religious and the poetical, we saw that the ambition of the rhetoric of glory, at the time of kings, mentioned in connection with the idea of greatness, was to impose another memory in place of that of Eris, Discord. The oath, this ritual of language - horkos conspiring with lethe — has perhaps disappeared from democratic and republican prose, but not from the city's praise of itself, with its euphemisms, its ceremonies, its civic rituals, its commemorations. Here, the philosopher will refrain from condemning the successive amnesties that the French Republic in particular has so often employed, but he will stress their purely utilitarian, therapeutic character. And he will listen to the voice of the unforgetting memory, excluded from the arena of power by the forgetful memory bound to the prosaic refounding of the political. At this price, the thin wall separating amnesty from amnesia can be preserved. The knowledge that the city remains "a divided city" belongs to practical wisdom and to its political exercise. The fortifying use of dissensus, the echo of the unforgetting memory of discord, contributes to this.

Our uneasiness concerning the right attitude to take with regard to the uses and abuses of forgetting, mainly in the practice of institutions, is finally the symptom of a stubborn uncertainty affecting the relation between forgetting and forgiveness on the level of its deep structure. The question returns with insistence: if it is possible to speak of happy memory, does there exist something like a happy forgetting? In my opinion, an ultimate indecisiveness strikes what could be presented as an eschatology of forgetting. We anticipated this crisis at the end of the chapter on forgetting by balancing forgetting through the effacement of traces against the forgetting kept in reserve. And it is once again a question of this balance within the horizon of a happy memory.

Why can one not speak of happy forgetting in precisely the same way we were able to speak of happy memory?

An initial reason is that our relation with forgetting is not marked by events of thinking comparable to the event of recognition, which we have called the small miracle of memory — a memory is evoked, it arrives, it returns, we recognize in an instant the thing, the event, the person and we exclaim: "That's her! That's him!" The arrival of a memory is an event. Forgetting is not an event, something that happens or that someone causes to happen. To be sure, we can notice that we have forgotten, and we remark it at a given moment. But what we then recognize is the state of forgetfulness we had been in. This state can, certainly, be termed a "force," as Nietzsche declares at the beginning of the second essay in On the Genealogy of Morals. This is, he says, "no mere vis inertide," "it is rather an active and in the strictest sense positive faculty of repression" (57). But how are we made aware of this power that makes forgetting "a doorkeeper, a preserver of psychic order, repose, and etiquette" (58)? We know it thanks to memory, that faculty "with the aid of which forgetfulness is abrogated in certain cases - namely in those cases where promises are made" (58). In these specific cases, one can speak not only of a faculty but of the will not to forget, "a desire for the continuance of something desired once, a real memory of the will" (58). It is in binding oneself that one unbinds oneself from what was a force, but not yet a will. It will be objected that the strategies of forgetting, which we spoke of above, consist in more or less active interventions, which can be denounced as responsible for omission, negligence, blindness. But if a moral guilt can be attached to the behaviors resulting from the class of non-action, as Karl Jaspers required in his Schuldfrage, this is because what are involved are a large number of punctual acts of non-acting, the precise occasions of which can be recalled after the fact.

A second reason for setting aside the idea of a symmetry between memory and forgetting in terms of success or accomplishment is that, with respect to forgiveness, forgetting has its own dilemmas. They have to do with the fact that, if memory is concerned with events even in the exchanges that give rise to retribution, reparation, absolution, forgetting develops enduring situations, which in this sense can be said to be historical, inasmuch as they are constitutive of the tragic nature of action. In this way action is prevented from continuing by forgetting, either by the intertwining of roles that are impossible to untangle, or by insurmountable conflicts in which the dispute is unresolvable, insuperable, or yet again by irreparable wrongs often extending back to far-distant epochs. If forgiveness has anything to do in these situations of growing tragedy, 2 it can only be a matter of a sort of nonpunctual work bearing on the manner of waiting for and welcoming typical situations: the inextricable, the irreconcilable, the irreparable. This tacit admission has less to do with memory than with mourning as an enduring disposition. The three figures evoked here are in fact three figures of loss. The admission that loss is forever would be the maxim of wisdom worthy of being held to be the incognito of forgiveness in the tragedy of action. The patient search for compromise would be its minor coin, but so would the welcoming of dissensus in the ethics of discussion. Must one go so far as to say "forget the debt," the figure of loss? Yes, perhaps, inasmuch as debt confines to fault and is enclosed within repetition. No, inasmuch as it signifies the recognition of a heritage. A subtle work of unbinding and binding is to be pursued at the very heart of debt: on one hand, being released from the fault, on the other, binding a debtor who is forever insolvent. Debt without fault. Debt stripped bare. Where one finds the debt to the dead and history as sepulcher.

The most irreducible reason for the asymmetry between forgetting and memory with respect to forgiveness resides in the undecidable character of the polarity that divides the subterranean empire of forgetting against itself: the polarity between forgetting through effacement and forgetting kept in reserve. It is with the admission of this irreducible equivocalness that the most precious and the most secret mark of forgiveness can come to be reg-istered. Admitting that "in human experience there is no superior point of view from which one could perceive the common source of destruction and of construction": such was, above, the verdict of the hermeneutics of the human condition with respect to forgetting. "Of this great drama of being," we said in conclusion, "there is, for us, no possible balance sheet." This is why there cannot be a happy forgetting in the same way as one can dream of a happy memory. What would be the mark of forgiveness on this admission? Negatively, it would consist in inscribing the powerlessness of reflection and speculation at the head of the list of things to be renounced, ahead of the ir-reparable; and, positively, in incorporating this renouncement of knowledge into the small pleasures of happy memory when the barrier of forgetting is pushed back a few degrees. Could one then speak of an ars oblivionis, in the sense in which an ars memoriae has been discussed on several occasions? In truth, the paths are difficult to trace out in this unfamiliar territory. I propose three tracks for our exploration. One could, after the manner of Harald Weinrich, to whom I owe the expression,53 develop this art in strict symmetry with the ars memoriae celebrated by Frances Yates. If the latter art was essentially a technique of memorization rather than an abandonment to remembering and to its spontaneous irruptions, the opposite art would be a "lethatechnique" (Lethe, 29). If it were, indeed, to follow the treatises on the mnemonic art contemporaneous with the ars memoriae, the art of forgetting would have to rest on a rhetoric of extinction: writing to extinguish-the contrary of making an archive. But Weinrich, too tormented by "Auschwitz and impossible forgetfulness" (253ff.), cannot subscribe to this barbarous dream. This sacking, which in another time was called an auto-da-fé, is traced out against the horizon of memory as a threat worse than forgetting through effacement. Is not this reduction to ashes, as a limit-experience, the proof by absurdity that the art of forgetting, if there is one, could not be constructed as a distinct project, alongside the wish for happy memory? What is then proposed in opposition to this ruinous competition between the strategies of memory and forgetting is the possibility of a work of forgetting, interweaving among all the fibers that connect us to time: memory of the past, expectation of the future, and attention to the present. This is the path chosen by Marc Augé in Les Formes de l'oubli.54 A subtle observer and interpreter of African rituals, he sketches three "figures" of forgetting that the rituals raise to the level of emblems. To return to the past, he says, one must forget the present, as in states of possession. To return to the present, one must suspend the ties with the past and the future, as in the games of role reversal. To embrace the future, one must forget the past in a gesture of inauguration, beginning, and rebeginning, as in rituals of initiation. And "it is always in the present, finally, that forgetting is conjugated" (78). As the emblematic figures suggest, the "three daughters" of forgetting (79) reign over communities and individuals. They are at one and the same time institutions and ordeals: "The relation to time is always thought in the singular-plural. This means that there must be at least two people in order to forget, that is to say, to manage time" (84). But, if "nothing is more difficult to succeed than a return" (84), as we have known since the Odyssey, and perhaps also than a suspension and a rebeginning, must one not try to forget, at the risk of finding only an interminable memory, like the narrator of Remembrance of Things Past? Must not forgetting, outsmarting its own vigilance, as it were, forget itself?

A third track is also offered for exploration: the path of a forgetting that would no longer be a strategy, nor a work, an idle forgetting. It would parallel memory, not as the remembrance of what has occurred, nor the memorization of know-how, not even as the commemoration of the founding events of our identity, but as a concerned disposition established in duration. If memory is in fact a capacity, the power of remembering (faire-mémoire), it is more fundamentally a figure of care, that basic anthropological structure of our historical condition. In memory-as-care we hold ourselves open to the past, we remain concerned about it. Would there not then be a supreme form of forgetting, as a disposition and a way of being in the world, which would be insouciance, carefreeness? Cares, care, no more would be said of them, as at the end of a psychoanalysis that Freud would define as "terminable." ..However, under pain of slipping back into the traps of amnesty-amnesia, ars oblivionis could not constitute an order distinct from memory, out of complacency with the wearing away of time. It can only arrange itself under the optative mood of happy memory. It would simply add a gracious note to the work of memory and the work of mourning. For it would not be work at all.

How could we not mention— echoing André Breton's apostrophe on the joy of memory and in counterpoint to Walter Benjamin's evocation of the angel of history with its folded wings-Kierkegaard's praise of forgetting as the liberation of care?

It is indeed to those who are full of cares that the Gospel's exhortation to "consider the lilies of the field and the birds of the air" is addressed 55 Kierkegaard notes, "Yet this is so only if the person in distress actually gives his attention to the lilies and the birds and their life and forgets himself in contemplation of them and their life, while in his absorption in them he, unnoticed, by himself learns something about himself" (161-62). What he will learn from the lilies is that "they do not work." Are we then to understand that the even the work of memory and the work of mourning are to be forgotten? And if they "do not spin" either, their mere existence being their adornment, are we to understand that man too "without working, without spinning, without any meritoriousness, is more glorious than Solomon's glory by being a human being"? And the birds, "sow not and reap not and gather not into barns." But, if "the wood-dove is the human being," how can he manage not to be "worried" and "to break with the worry of comparison" and "to be contented to be a human being" (182)?

What "godly diversion" (184), as Kierkegaard calls "forgetting the worry" to distinguish it from ordinary distractions, would be capable of bringing man "to consider: how glorious it is to be a human being" (187)?

Carefree memory on the horizon of concerned memory, the soul common to memory that forgets and does not forget.

Under the sign of this ultimate incognito of forgiveness, an echo can be heard of the word of wisdom uttered in the Song of Songs: "Love is as strong as death." The reserve of forgetting, I would then say, is as strong as the forgetting through effacement.

Under history, memory and forgetting.

Under memory and forgetting, life.

But writing a life is another story.

Incompletion.

- Paul Ricoeur