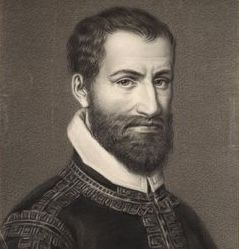

帕萊斯特里那 Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525 or 1526-1594)

帕萊斯特里那生於名為帕菜斯特里那Palestrina的小鎮,在附近的羅馬充當唱詩班男童,並接受音樂教育。他在那兒充當教堂樂手七年之後,於1551年成為聖伯多祿大殿的朱莉亞小教堂的唱詩班指揮。 他把自己的第一本彌撒曲集(1554)獻給了他的贊助人教宗儒略三世。1555年,他短期充當教宗官方的西斯廷小教堂的歌手,但因為已婚而不得不放棄這一榮譽。他在羅馬度過了事業中剩餘的四十年,擔任過兩個重要教堂——拉特朗聖若望大殿和聖母大殿的唱詩班指揮,還擔任新成立的耶穌會神學院的教師。從 1571 年到他1594年逝世時,他再次擔任了朱莉亞小教堂的唱詩班指揮。

帕萊斯特里那曾兩次拒絕要他離開羅馬的建議,一次是1568年來自皇帝馬克西米里安二世的聘請(後來由菲利普•德•蒙特Philippe de Monte任這一職位),另一次是1583年來自曼圖亞的大公古列爾莫•貢扎加Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga in Mantua,他後來為貢扎加寫過9首彌撒曲。

帕萊斯特里那晚年負責審查對官方聖詠書的修訂,以使它符合特倫托大公議會所命令的各種改變。他的工作就是從聖詠中清除“粗俗的、模糊的、矛盾的和冗贅的東西”,按照教皇格里高利十三世的說法,這些東西是“由於作曲家、抄譜員和印刷工人的笨拙、疏忽,甚至邪惡所造成的”。這一工作在帕萊斯特里那生前並未完成,而是由其他人來續成的。《循序經本 Graduale Romanum》的梅迪奇版在1614年出版,它一直沿用到 1908 年,由法國索萊姆修道院(Solesmes)的僧侶出版梵蒂岡版時止。

帕菜斯特里那的絕大部分作品都是宗教性的。他寫過104 首彌撒曲,大約250首經文歌,許多其他的宗教禮儀作品,以及約50首意大利語歌詞的宗教牧歌。他的世俗牧歌(約100首)在技巧上是嫻熟的,但趨於保守。即使是這樣,帕菜斯特里那後來還是承認,為愛情詩歌寫音樂是“羞愧和傷心的”。

帕萊斯特里那風格

帕萊斯特里那被稱為“音樂的王子”,他的作品是“絕對完美”的宗教風格。他比其他作曲家強的地方是,他完全掌握了反宗教改革的嚴肅和保守的本質。他死後不久,人們就普遍談論“帕萊斯特里那風格”了,把這當成復調宗教音樂的一個標準。的確,講授對位方法的各種書籍中,從富克斯 Johann Joseph Fux 的《藝術津梁 Gradus ad Parnassum》(1725)到更近代的教科書,目的都在於引導青年作曲家重建這種風格。

帕萊斯特里那研究了著名的法-佛蘭德作曲家的作品,並完全掌握了他們的技巧。他半數的彌撒曲是根據復調模式寫成的,而這種模式大多數都是由前輩主要的對位學家所創立。有11首這樣的模式收入《花之經文歌Motetti del fiore》兩卷本中,由雅克•莫代爾納(約1495—1562,法國音樂出版商)出版於 1532年和1538年。

帕萊斯特里那為少數彌撒曲使用了老式的定旋律cantus firmus方法(包括他根據傳統的《武裝的人》旋律創作的兩首中的前一首),但是,他一般喜歡用所有聲部來解釋聖詠,而不限於用男高音聲部。讓人想起更古老的法一佛蘭德傳統的其他作品,有彌撒曲《追逸》(Missa ad fugam),全部寫成二重卡農canon;還有他1570年的彌撒曲《充滿我的臉》(Repleatur os meum),系統地介紹了每一個音程上的卡農,從八度下行至同度,在最後的《羔羊經》中以一段二重卡農結束。在帕萊斯特里那晚期的彌撒曲中也出現卡農,雖然很少像這兩首貫徹得如此嚴格。帕萊斯特里那最大的一組彌撒曲是模仿彌撒曲,很多來自其他作曲家的復調polyphonic作品,只有少數來自他自己的經文歌motets和牧歌madrigal。

帕萊斯特里那的單個聲部有近乎素歌的性質,它們的曲線往往是拱形的,運動motion則多半是級進,有短小的、偶爾的跳進。例如,在著名的《馬切魯斯Marcellus教皇彌撒曲》中的第一首《羔羊經》中,我們看到氣息悠長、吐字靈活和易於歌唱的線條,大部分處在九度的範圍內。少數大於三度的跳進,由於返回跳進音程以內的一個音而有所緩和。 重復音很少見,而且節奏單位在長度上有變化。線條的流暢同對自然音調式的忠實相匹配。帕萊斯特里那刻意地避免變化音體系,甚至在他的世俗牧歌里也如此,在他的宗教音樂,尤其是彌撒曲中就是更如此了。他只接受偽音musica ficta常規所要求的必要的半音變化。

帕萊斯特里那對位法的許多細節,都符合扎里諾Zarlino在其《和聲規範》中所傳播的維拉爾特Willaert學派的教導。音樂幾乎完全寫成參拍子的,在原來的版本中,它包括每一個全音符的下拍和上拍。獨立的線條可以在每一拍的完整的三和弦中相遇。這種常規在採用留音suspensions時被打破,在留音中,在上拍時一個聲部與其他聲部是協和的,但是在下拍時一個以上的其他聲部形成不協和音程與它相對,而且延留音聲部下行一級解決。這種緊張和鬆弛的交替 —-下拍強烈的不協和同上拍甜美的協和的交替 —多於重音音節的反復出現,賦予音樂一種鐘擺似的律動。如果在運動著的聲部採用級進方式,不協和音在拍子之間就可能產生。帕菜斯特里那對於這一規則的唯一例外就是後來所謂的“駢枝法”(cambiata)。在這種方法中,一個聲部從一個不協和音向下跳進三度,達到一個協和音,而不是用級進的方法。

圓潤的自然音線條diatonic lines和對不協和音的謹慎處理,賦予帕萊斯特里那的音樂一貫的寧靜和清澈。他的對位線條的另一積極性質,就是各個聲部垂直的結合。通過聲部組合和間距的變化,使同一個和聲產生大量微妙的不同層次和音色。 帕萊斯特里那音樂的節奏,以及16 世紀復調的一般節奏,都是一種單獨聲部的節奏加上由拍子上的和聲所產生的聚合節奏的混合物。當每個聲部根據自身天然的節奏用小節隔開時,我們就能清楚地看到單獨聲部的線條是如何的獨立。但是,當這一作品被演奏,所有聲部都一塊響起時,我們就能覺察到2/2或4/4“拍子”的相當規則的連續,它們大多數是由和聲的變化和強拍的延留音而引起的。這一點標誌著帕萊斯特里那風格所特有的節奏的規律性。

在西方音樂史中,帕萊斯特里那的風格是第一個為後世有意識地作為一種範本而加以保留、分離和模仿的風格。當17世紀的音樂家們談論“古風格”(或“嚴肅風格”)時,他們心目中的恰恰就是這種風格。

【文本來源:Donald Jay Grout_ Claude Victor Palisca- 西方音乐史-人民音乐出版社(2010)(第六版) 第198-204頁】

Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525 or 1526-1594), born in the small town of Palestrina, served as a choirboy and received his musical education in nearby Rome. After seven years there as a church musician, he became choirmaster of the Cappella Giulia at St. Peter's in 1551. He dedicated his first book of Masses (1554) to his patron, Pope Julius III. In 1555 he served briefly as a singer in the Cappella Sistina, the pope's official chapel, but had to relinquish the honor because he was married. He spent the remaining forty years of his career in Rome as choirmaster at two important churches, St. John Lateran and Santa Maria Maggiore, as teacher at a newly founded Jesuit Seminary, and once again as choirmaster of the Cappella Giulia, from 1571 until his death in 1594.

Palestrina refused two offers which would have taken him away from Rome: one from Emperor Maximilian II in 1568 (Philippe de Monte eventually took this position) and another in 1583 from Duke Guglielmo Gonzaga in Mantua, for whom he later wrote nine Masses. During the latter part of his life, Palestrina supervised the revision of the official chant books to accord with the changes ordered by the Council of Trent. His task was to purge the chants of "barbarisms, obscurities, contrari-eties, and superfluities" acquired, according to Pope Gregory XIII, "as a result of the clumsiness or negligence or even wickedness of the composers, scribes, and printers." This work, not completed during Palestrina's lifetime, was completed by others, and the Medicean edition of the Gradual was published in 1614. It remained in use until the Vatican Edition, published by the monks of Solesmes, appeared in 1908.

By far the greatest part of Palestrina's work was sacred. He wrote 104 Masses, about 250 motets, many other liturgical compositions, and some 50 spiritual madrigals with Italian texts. His secular madrigals (approximately 100) are technically polished but conservative; even so, Palestrina later confessed that he "blushed and grieved" to have written music for love poems.

The Palestrina Style

Palestrina has been called "the Prince of Music" and his works the "absolute perfection" of church style. Better than any other composer, he captured the essence of the sober, conservative aspect of the Counter-Reformation. Not long after he died it was common to speak of the "stile da Palestrina," the Palestrina style, as a standard for polyphonic church music. Indeed, counterpoint instruction books, from Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum (1725) to more recent texts, have aimed at guiding young composers to recreate this style.

Palestrina studied the works of outstanding Franco-Flemish composers and completely mastered their craft. Half of his Masses are based on polyphonic models, many of them by leading contrapuntists of previous generations. Eleven of these models are found in Motetti del fiore, two collections published by Jacques Moderne in 1532 and 1538.

Palestrina used the old-fashioned cantus firmus method for a few of his Masses (including the first of two he wrote on the traditional L'homme armé melody), but he generally preferred to paraphrase the chant in all the parts rather than confine it to the tenor voice. Other works reminiscent of the older Flemish tradition are his early Missa ad fugam, written throughout in double canon, and his Mass Repleatur os meum of 1570, which systematically introduces canons at every interval from the octave down to the unison, ending with a double canon in the last Agnus Dei. Canons also occur in Palestrina's later Masses, though seldom carried through so rigorously as in these two works. The largest group of Palestrina's Masses are imitation masses, many derived from polyphonic compositions by other composers, a smaller number on his own motets and madrigals.

Palestrina's individual voice parts have an almost plainsong-like quality; their curve often describes an arch, and the motion is mostly stepwise, with short, infrequent leaps. In the first Agnus Dei from the famous Pope Marcellus Mass for example, we observe long-breathed, flexibly articulated, easily singable lines, staying for the most part within the range of a ninth. The few leaps greater than a third are smoothed over by a return to a note within the interval of the skip. There are few repeated notes, and the rhythmic units vary in length. Fluency of line is matched by fidelity to the diatonic modes. Palestrina studiously avoided chromaticism even in his secular madrigals, the more so in his sacred works, and above all in the Masses. He admitted only the essential alterations demanded by the conventions of musica ficta.

Palestrina's counterpoint conforms in most details with the teachings of Willaert's school as transmitted by Zarlino in his Le istitutioni harmoniche. The music is written almost entirely in the alla breve measure of ¢, which in the original editions consists of a downbeat and upbeat of one semibreve each. The independent lines are expected to meet in a full triad on each beat. This convention is broken for suspensions, in which a voice is consonant with the other parts on the upbeat, but one or more of the other parts makes a dissonance against it on the downbeat, and the suspended voice resolves a step down. This alternation of tension and relaxation - strong dissonance on the downbeat and sweet consonance on the upbeat - more than the recurrence of accented syllables, endows this music with a pendulum-like pulse. Dissonances between beats may occur if the voice that is moving does so in a stepwise fashion. Palestrina's only exception to this rule is the cambiata, as it was later called, in which a voice leaps a third down from a dissonance to a consonance instead of approaching it by step.

The smooth diatonic lines and the discreet handling of dissonance give Palestrina's music a consistent serenity and clarity. Another positive quality of his counterpoint lies in the vertical combination of the voices. By varying the voice grouping and spacing, the same harmony produces a large number of subtly different shadings and sonorities.

The rhythm of Palestrina's music — and that of sixteenth-century polyphony in general — is a mixture of the rhythms of the individual voices plus a collective rhythm resulting from the harmonies on the beats. When each voice is barred according to its own natural rhythm, we can see graphically how independent the individual lines are. But when the piece is performed and all the voices are sounding together, we perceive a fairly regular succession of 2 or 4 "measures" that are set off mostly by the harmonic changes and the suspensions on strong beats. This gently marked regularity of rhythm characterizes the Palestrina style.

Palestrina's style was the first in the history of Western music to be con sciously preserved, isolated, and imitated as a model in later ages. It is this style that seventeenth-century musicians had in mind when they spoke of stile antico (old style) or stile grave (severe style).

[Source: Donald Jay Grout_ Claude V. Palisca - A history of western music-6th Edition - Norton (2001),pp. 235-240]