弗洛伊德 《自我与本我》 Ego & Id

病理學的探索使我們的興趣全部集中於被壓抑的東西上

Pathological research has directed our interest too exclusively to the repressed.

自我、本我、超我 / 意識、無意識、前意識

ego, id, super-ego /consciousness, unconsciousness, preconsciousness

每個個人都有一個心理過程的連貫組織;我們稱之為他的自我 ego。意識 Cs=consciousness就隸屬於這個自我 ;自我控制著活動的方法—就是說,控制著進人外部世界的興奮發射; 自我是管理著它自己所有的形成過程的心理力量,在夜間入睡,雖然它即使在入睡的時候也對夢進行稽查。壓抑也是從這個自我發生的。通過壓抑,自我試圖把心理中的某些傾向不僅從意識中排斥出去,而且從其他效應和活動的形式中排斥出去。在分析中,這些被排斥的傾向處在自我的對立面。分析面臨著一個任務,就是去掉抗拒,自我正是用它來表示自己與被壓抑的東西無關。p.202

We have formed the idea that in each individual there is a coherent organization of mental processes; and we call this his ego. It is to this ego that consciousness is attached; the ego controls the approaches to motility(運動性)-that is, to the discharge of excitations into the external world; it is the mental agency which supervises all its own constituent processes, and which goes to sleep at night, though even then it exercises the censorship on dreams. From this ego proceed the repressions, too, by means of which it is sought to exclude certain trends in the mind not merely from conscious ness but also from other forms of effectiveness and activity. In analysis these trends which have been shut out stand in opposition to the ego, and the analysis is faced with the task of removing the resistances which the ego displays against concerning itself with the repressed. p.8

並不是所有的無意識 Ucs=unconsciousness,都是被壓抑的。自我的一個部分 多麼重要的一個部分啊—也可能是無意識,毫無疑問是無意識。屬於自我的這個無意識不像前意識 Pcs=preconsciousness那樣是潛伏的;因為如果它是潛伏的話,那麼它不變成意識就不能活動,而且使它成次意識的過程也不會遭到這樣巨大的困難。當我們發現我們面對著假設第三個不是被壓抑的無意識的必要性時,我們必須承認 “處於無意識中”這個特徵對於我們開始喪失了。 p.203

but not all that is Ucs. is repressed. A part of the ego, too-and Heaven knows how important a part-may be Ucs., undoubtedly is Ucs. And this Ucs. belonging to the ego is not latent like the Pcs. ; for if it were, it could not be activated without becoming Cs., and the process of making it conscious would not encounter such great difficulties. When we find ourselves thus confronted by the necessity of postulating a third Ucs., which is not repressed, we must admit that the characteristic of being unconscious begins to lose significance for us.

p.9

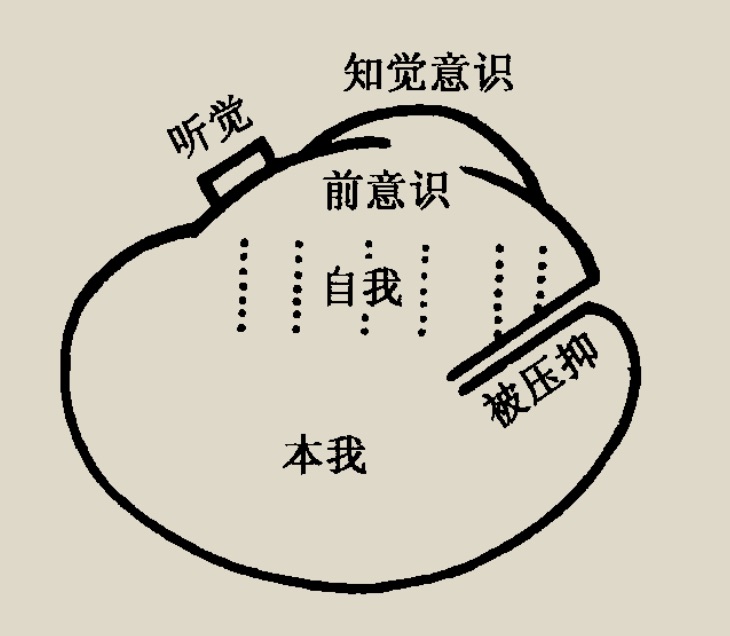

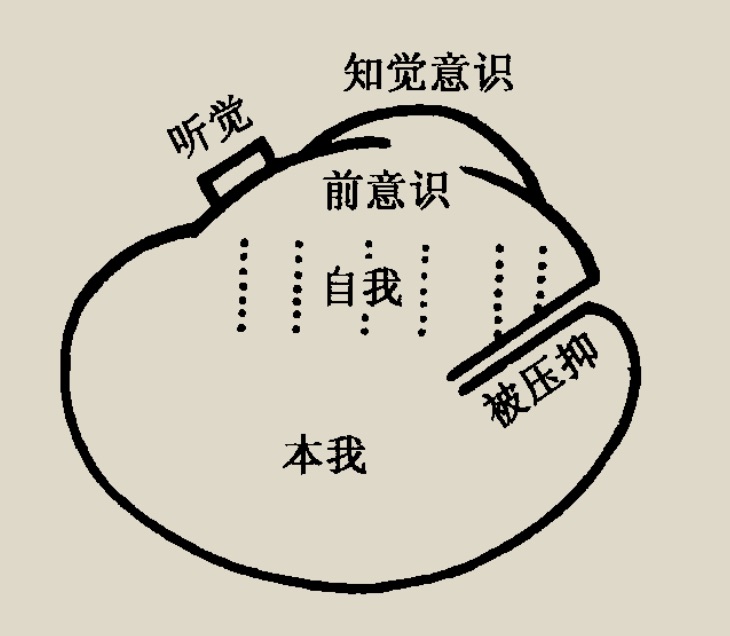

我們很快就將看到,為了描寫或理解,我們是否能夠從這個觀點中獲得一些好處。現在,我們將把一個個體看作未知的和無意識的心理的本我 id,自我依託在它的表層,知覺系統從它的內核中發展出來。如果我們努力對它進行形象化的描述,我們可以補充說自我並不全部包住本我,而只是包住了一個範圍,在這個範圍里知覺系統構成了它的[自我的]表層,多少有些像胚盤依託在卵細胞上一樣。自我並不與本我明顯地分開;它的較低級的部分併入本我。

We shall soon see whether we can derive any advantage from this view for purposes either of description or of under standing. We shall now look upon an individual as a psychical id, unknown and unconscious, upon whose surface rests the ego, developed from its nucleus the Pcpt. system. If we make an effort to represent this pictorially, we may add that the ego does not completely envelop the id, but only does so to the extent to which the system Pcpt. forms its [the ego's] surface, more or less as the germinal disc rests upon the ovum. The ego is not sharply separated from the id; its lower portion merges into it.

但是被壓抑的東西也併入本我,並且僅僅作為它的一個部分。被壓抑的東西只是由於壓抑的抗拒而與自我截然分開;它能夠通過本我與自我相通。我們立刻瞭解到,幾乎所有我們在病理學的教唆下所划定的分界線僅僅與心理器官的表層 — 我們唯一知道的那些部分 — 有關。我們已描述過了的這些東西的狀態可以用圖表述如下;雖然必須承認我們選擇的這個形式並不打算到處套用,它只不過是用來說明問題而已。 p.212

But the repressed merges into the id as well, and is merely a part of it. The repressed is only cut off sharply from the ego by the resistances of repression; it can communicate with the ego through the id. We at once realize that almost all the lines of demarcation we have drawn at the instigation of pathology relate only to the superficial strata of the mental apparatus-the only ones known to us. The state of things which we have been describing can be represented diagrammatically (Fig. 1); though it must be remarked that the form chosen has no pretensions to any special applicability, but is merely intended to serve for purposes of exposition.p.17-18

自我功能的重要性表現在下面這一事實上,即在正常情況下,對能動性的控制移歸自我掌握。這樣,在它與本我的關係中,它就像騎在馬背上的人,他必須牽制著馬的優勢力量;所不同的是:騎手試圖用自己的力量努力去牽制,而自我則使用借來的力量。這個類比還可以進一步引申。假如騎手沒有被馬甩掉,他常常是不得不引它走向它所要去的地方;同樣,自我習慣於把本我的慾望轉變為行動,好像這種慾望是它自己的慾望似的。

The functional importance of the ego is manifested in the fact that normally control over the approaches to motility devolves upon it. Thus in its relation to the id it is like a man on horseback, who has to hold in check the superior strength of the horse; with this difference, that the rider tries to do so with his own strength while the ego uses borrowed forces. The analogy may be carried a little further. Often a rider, if he is not to be parted from his horse, is obliged to guide it where it wants to go; so in the same way the ego is in the habit of transforming the id's will into action as if it were its own.

除了知覺系統的影響以外,另一個因素好像在形成自我和造成它從本我分化出來中起著作用。一個人自己的軀體,首先是它的外表,是一個可以產生外部知覺和內部知覺的地方。它像任何其他對象那樣被看到,但是對於觸覺,它產生兩種感覺,其中一個可能與內部知覺相等。心理生理學已經充分討論了一個人自己的軀體在知覺世界的其他對象中獲得它特殊位置的方式。在這個過程中,疼痛好像也起了作用,在疼痛中我們獲得我們器官的新知識,這個方式也許是般我們得到我們軀體觀念的典型方法。

nother factor, besides the influence of the system Pcpt., seems to have played a part in bringing about the formation of the ego and its differentiation from the id. A person's own body, and above all its surface, is a place from which both external and internal perceptions may spring. It is seen like any other object, but to the touch it yields two kinds of sensations, one of which may be equivalent to an internal perception. Psycho-physiology has fully discussed the manner in which a person's own body attains its special position among other objects in the world of perception. Pain, too, seems to play a part in the process, and the way in which we gain new knowledge of our organs during painful illnesses is perhaps a model of the way by which in general we arrive at the idea of our body.

自我首要地是軀體的自我(bodily ego);它不僅僅是一個表面的實體,而且本身即是表面的投影。如果我們希望找出它在解剖上的類比,我們最好能使它和解剖學者們的“大腦皮層人像”(cortical homunculus)等同起來,這個“大腦皮層人像” 倒立於皮質之中,腳踵上舉,面孔朝後,就像我們所知道的,他的言語區域在左手那邊。 自我與意識的關係已被再三討論過了;在這一方面還有一些重要的事實需要在這裡闡述。雖然我們無論到哪兒都帶著我們的社會的或倫理的價值標準,但是,當聽到較低級的感情的行動舞台是在無意識之中,我們並不感到驚訝;而且我們希望在我們的價值標準中排列得越高的心理功能,能夠越容易地找到通向意識的道路,從而得到保證。但是,這裡,精神分析的經驗使我們失望。一方面我們確實發現:甚至通常要求強烈反思的微妙的和困難的智力操作同樣能夠前意識地進行而不進人意識。這類例子相當確鑿;例如,它們可以在睡眠狀態中發生,就像事實表明的,某人醒後立刻發現他知道了某個困難的數學題或其他問題的答案,對這個答案,他前一天苦苦思索而徒勞無效。

The ego is first and foremost a bodily ego; it is not merely a surface entity, but is itself the projection of a surface. If we wish to find an anatomical analogy for it we can best identify it with the 'cortical homunculus' of the anatomists, which stands on its head in the cortex, sticks up its heels, faces backwards and, as we know, has its speech-area on the left-hand side.

The relation of the ego to consciousness has been entered into repeatedly; yet there are some important facts in this connection which remain to be described here. Accustomed as we are to taking our social or ethical scale of values along with us wherever we go, we feel no surprise at hearing that the scene of the activities of the lower passions is in the unconscious; we expect, moreover, that the higher any mental function ranks in our scale of values the more easily it will find access to consciousness assured to it. Here, however, psycho-analytic experience disappoints us. On the one hand, we have evidence that even subtle and difficult intellectual operations which ordinarily require strenuous reflection can equally be carried out preconsciously and without coming into consciousness. Instances of this are quite incontestable; they may occur, for example, during the state of sleep, as is shown when someone finds, immediately after waking, that he knows the solution to a difficult mathematical or other problem with which he had been wrestling in vain the day before.

但是,有另外一個現象,一個更為奇怪的現象。在分析中我們發現有一些人的自我批評和良心的官能—這是一些極高級的心理活動—是無意識的而且無意識地產生最重要的結果;因此在分析中抗拒屬於無意識的例子並不是獨一無二的。但是這個新發現不顧我們良好的批評判斷,迫使我們談論一種“無意識罪惡感”,它比其他發現更加使我們感到困惑,並給我們提出一些新問題,特別是當我們逐漸看到了在大量的神經症病例中這一類無意識罪惡感起了決定性的經濟作用,並且在復原的道路上設置了最強有力的障礙。如果我們再次回到我們的價值標準上,我們將不得不說在自我中,不僅最低級的東西,而且最高級的東西都可以是無意識的。就像我們對我們剛剛說過的意識自我(conscious ego) 擁有一種證據一樣:自我首要地是一種軀體自我。p.214-216

There is another phenomenon, however, which is far stranger. In our analyses we discover that there are people in whom the faculties of self-criticism and conscience- mental activities, that is, that rank as extremely high ones are unconscious and unconsciously produce effects of the greatest importance; the example of resistance remaining unconscious during analysis is therefore by no means unique. But this new discovery, which compels us, in spite of our better critical judgment, to speak of an 'unconscious sense of guilt', bewilders us far more than the other and sets us fresh problems, especially when we gradually come to see that in a great number of neuroses an unconscious sense of guilt of this kind plays a decisive economic part and puts the most powerful obstacles in the way of recovery. If we come back once more to our scale of values, we shall have to say that not only what is lowest but also what is highest in the ego can be unconscious. It is as if we were thus supplied with a proof of what we have just asserted of the conscious ego: that it is first and foremost a body-ego.

P.19-21

如果我們再次考慮如前所述的超我 super-ego的起源,我們會發現這是兩個非常重要的因素的結果,一個是生物本性,另一個是歷史本性,即:人類童年期無助和依賴的漫長過程,他的奧狄帕司情結(Oedipus complex)的事實(我們已經說明,對奧狄帕司情結的壓抑與潛伏 階段之前力比多發展的中斷有關,同樣也和一個人的性生活的雙相性起源有關)。按照一個精神分析的假設,最後所提到的好像為人所特有的這個現象是冰河時期必然引起的文化發展的遺產。因此我們看到超我從自我分化出來並非偶然;這種分化代表著個人發展和種系發展的最重要的特性;確實,通過把父母的影響看作永久性的東西,這種分化才使得上述那些因素—這些因素是這種分化的起源—能永久存在下去。

If we consider once more the origin of the super-ego as we have described it, we shall recognize that it is the out come of two highly important factors, one of a biological and the other of a historical nature: namely, the lengthy duration in man of his childhood helplessness and dependence, and the fact of his Oedipus complex, the repression of which we have shown to be connected with the interruption of libidinal development by the latency period and so with the diphasic onset of man's sexual life.16 According to one psycho-analytic hypothesis, the last-mentioned phenomenon, which seems to be peculiar to man, is a heritage of the cultural development necessitated by the glacial epoch. We see, then, that the differentiation of the super ego from the ego is no matter of chance; it represents the most important characteristics of the development both of the individual and of the species; indeed, by giving permanent expression to the influence of the parents it perpetuates the existence of the factors to which it owes its origin.

精神分析學曾多次被指責忽視了人性高級的、道德的、超個人方面。這種指責無論在歷史上還是在方法上都是不公正的。首先,因為從一開始我們就把慫恿壓抑的功能歸於自我中的道德和美的趨勢,其次,這種指責是對一種認識的總的否定,這種認識認為精神分析的研究不能像哲學體系一樣產生一個完整的、現成的理論結構,而必須通過對正常和反常的現象進行分析的解剖來尋找逐步通向理解複雜心理現象的道路。只要我們關心心理生活中被壓抑東西的研究,我們就完全沒有必要擔心找不到人的高級方面的東西。但是,既然我們已經著手對自我進行分析,我們就能夠回答所有那些道德感受到打擊的人和那些抱怨說人確實必須有個高級本性的人:“非常正確,”我們可以說,“正是在這個自我典範或超我中,我們具有那個高級本性,它是我們與父母關係的代表。當我們還是小孩時,我們就知道那些高級本性,我們羨慕它們,也害怕它們;之後我們就把它們納為己有。”

Psycho-analysis has been reproached time after time with ignoring the higher, moral, supra-personal side of human nature. The reproach is doubly unjust, both historically and methodologically. For, in the first place, we have from the very beginning attributed the function of instigating repression to the moral and aesthetic trends in the ego, and secondly, there has been a general refusal to recognize that psycho-analytic research could not, like a philosophical system, produce a complete and ready-made theoretical structure, but had to find its way step by step along the path towards understanding the intricacies of the mind by making an analytic dissection of both normal and abnormal phenomena. So long as we had to concern ourselves with the study of what is repressed in mental life, there was no need for us to share in any agitated apprehensions as to the whereabouts of the higher side of man. But now that we have embarked upon the analysis of the ego we can give an answer to all those whose moral sense has been shocked and who have complained that there must surely be a higher nature in man: 'Very true,' we can say, 'and here we have that higher nature, in this ego ideal or super-ego, the representative of our relation to our parents. When we were little children we knew these higher natures, we admired them and feared them; and later we took them into ourselves.'

因此,自我典範是奧狄帕司情結的繼承者,這樣,它也是本我的最強大的衝動和最重要的力比多變化的表現。通過自我典範的建立,自我已控制了奧狄帕司情結,同時還使自己掌握了對本我的統治權。自我基本上是外部世界的代表、現實的代表,超我則作為內部世界和本我的代表與自我形成對照。正如我們即將看到的,自我與超我之間的衝突最終將反映為現實的東西和心理的東西、外部世界和內部世界之間的懸殊差別。

通過理想的形成,生物學以及人種的變遷在本我中所建立起來的、並且遺留在本我之中的東西被自我所接管並在與自我的關係中作為個體被自我再次體驗。由於自我典範形成的方式,自我典範與每個個人的種系發生的獲得物—他的古代遺產—一有著最豐富的聯繫。通過理想形成,屬於我們每個人的心理生活的最低級部分的東西發生了改變,根據我們的價值尺度變為人類心理的最高級部分的東西。但是,甚至在我們確定了自我位置的意義上,企圖來確定自我典範的位置仍將是徒勞的,或者利用描繪自我與本能之間關係的方法來作類比,也是徒勞的。

The ego ideal is therefore the heir of the Oedipus complex, and thus it is also the expression of the most powerful impulses and most important libidinal vicissitudes of the id. By setting up this ego ideal, the ego has mastered the Oedipus complex and at the same time placed itself in subjection to the id. Whereas the ego is essentially the representative of the external world, of reality, the super-ego stands in contrast to it as the representative of the internal world, of the id. Conflicts between the ego and the ideal will, as we are now prepared to find, ultimately reflect the contrast between what is real and what is psychical, between the external world and the internal world.

Through the forming of the ideal, what biology and the vicissitudes of the human species have created in the id and left behind in it is taken over by the ego and re-experienced in relation to itself as an individual. Owing to the way in which the ego ideal is formed, it has the most abundant links with the phylogenetic acquisition of each individual-his archaic heritage. What has belonged to the lowest part of the mental life of each of us is changed, through the formation of the ideal, into what is highest in the human mind by our scale of values. It would be vain, however, to attempt to localize the ego ideal, even in the sense in which we have localized the ego,18 or to work it into any of the analogies with the help of which we have tried to picture the relation between the ego and the id.

表明自我典範適應人們所期望的人的任何高級本性是容易的。作為一個渴望成為父親的代替物,它包含著萌發了所有宗教的胚芽。表明自我達不到它的理想的自我鑒定,產生了謙卑的宗教感,信徒在這種宗教感中提出他渴望的申求。當一個孩子成長起來,父親的角色由教師或其他權威人士擔任下去;他們的禁令和禁律在自我典範中仍然強大,且繼續發展,並形成良心,履行道德的稽查。良心的要求和自我的現實行為之間的緊張狀態被體驗成一種罪惡感。社會感情在自我典範的基礎上通過與他人的自居作用而建立起來。p.226-228

It is easy to show that the ego ideal answers to everything that is expected of the higher nature of man. As a substitute for a longing for the father, it contains the germ from which all religions have evolved. The self-judgement which declares that the ego falls short of its ideal produces the religious sense of humility to which the believer appeals in his longing. As a child grows up, the role of father is carried on by teachers and others in authority; their injunctions and prohibitions remain powerful in the ego ideal and continue, in the form of conscience, to exercise the moral censorship. The tension between the demands of conscience and the actual performances of the ego is experienced as a sense of guilt. Social feelings rest on identifications with other people, on the basis of having the same ego ideal. p.31-33

【文本來源:

自我与本我/(奥)弗洛伊德(Freud, S.)著;林尘,张唤民.陈伟奇译.一上海:上海译文出版社,2011.9

Sigmund Freud THE EGO AND THE ID TRANSLATED BY Joan Riviere REVISED AND EDITED BY James Strachey WITH A BIOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION BY Peter Gay W. W. NORTON & COMPANY New York • London, 1960】