Feudal

System and the Hundred Years War

- Yip

Chee Hau

Introduction

This paper would discuss the relationship between the feudal system and the Hundred Years War. It comprises of six parts, namely, a glimpse at the feudal system, the changing feudal system during Capetian Dynasty, the immediate cause and the end of Hundred Years War respectively, the analysis between the feudal system and the Hundred Years War, and the conclusion.

A

Glimpse at the Feudal System

Feudalism in the strict sense of the term means those links between man and man, going down from suzerain of suzerains (formerly the emperor, then the king) to the very last of the vassals. In this hierarchy, only knights and nobles were included; commoners and villains always remained outsiders, although clerics might have rank.[1]

In feudal system of

In practice, notwithstanding that dukes and

counts were the vassals of the king, they were virtually independent. It was quite common that they did not

obey the king. The fief was at

first given only for the lifetime of the vassal, but it quickly became

hereditary. The land under the possession

of the duke was passed to his descendants rather than reverting to the

king. Therefore, when a noble

declared himself to be the vassal of the king, he nominally gave up his land

and then the king re-allotted the land to him. Besides, a vassal could have more than

one seigneur. For instance, around

1150 the Count of Champagne was the vassal of ten different seigneurs

(including the King of

The vassals themselves fell into the habit of parceling it out among their sons, which increased feudal fragmentation and caused a certain impoverishment of some of the petty lords who were more vulnerable to be attacked by the greater lords.

In this system, political authority had devolved into bonds of personal loyalty and dependence between the powerful (the seigneurs) and the weak (the vassals). Power in this age was exercised especially through land ownership. The surest way for the nobility to build a powerful army was to promise land to the mounted warriors. By doing an act of “homage[3]”, a warrior, or knight, could be “invested” with land. Once the land was given, the new owner in essence became “lord” (seigneur) over the peasants and townspeople within his territory. In effect, he exercised all the function related to the government- especially police and judicial functions. The only other local official at the local level was the parish priest.

Besides fidelity, the duties of the vassal were defined in two words: consilium and auxilium. The first means participation in the court and council of the sovereign, thus in his justice. The second entails military aid, joining the army of the lord as he requested, though the obligation was quickly limited to forty days. Auxilium also entailed financial aid in the so-called ‘four cases’: the ransom of a captured lord, the wedding of his eldest daughter, the knighting of his eldest son, and the lord’s departure on a Crusade.[4]

Marriage can be regarded as a strategy to

form cohesion with powerful allies.

In contrast with

Another characteristic of medieval

Survival depended on the skilled use of arms; given the basic equipment, ability might be more important than birth. There was no class barrier to a military career. Even a lord of a modest estate might provide a horse and secure an opening for an active, abled-bodied son. However, lives were tough for the young boys. A group of brothers from a Giroie family were taken to be trained. The eldest son, Arnold had a fatal fall during a friendly wrestling match. Hugh, the sixth son, was injured by a badly thrown weapon when he was practicing hurling javelins. Fulk, another of Giroie brothers, while serving as the bodyguard of Count Gilbert of Brionne, was murdered together with his lord.[6]

The nobles as well as the king, regarded the

land inherited as their own or their families. Therefore, they felt comfortable to

divide their land among his descendants and fellows. In doing so, the inhabitants within his

territory were not taken into consideration. For instance, Louis the Pious divided

his kingdom among his three sons, and Charles the Fat made a peace treaty with the

Feudal

System during the Capetian Dynasty

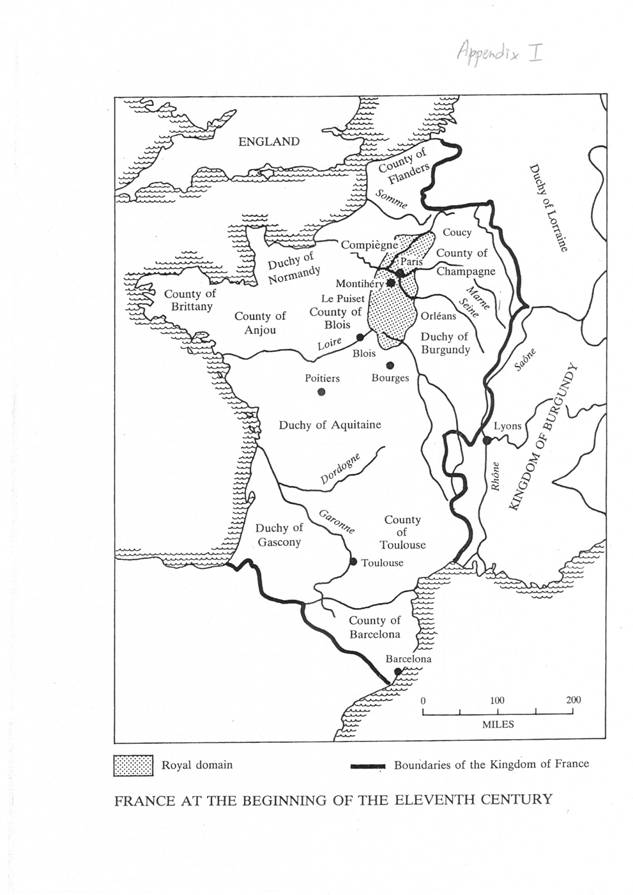

Since the end of Carolingian dynasty and the

beginning of Capetian dynasty, the royal influence gradually declined. The lords of

To strengthen the royal power, the establishment of a military and political dominance over princes and nobles who remained royal vassals was necessary. It required the development of the administrative, financial, judicial and military systems to assert, and subsequently, to maintain the royal power. The pre-requisite of such establishment was monetary resources. The Capetians were lucky enough to benefit from the location of their territories in a fertile region crossed by waterway and roads. The financial power was strengthened simultaneously by the growth of economic activities together with the growth of population. Increased economic activities resulted in the growth of revenue from royal domain, from feudal dues and the administration of justice, tolls and taxes. The increase in royal revenue allowed the development of a salaried and development bureaucracy and powerful armies, as well as the construction of stone fortresses.

The growth of population and of economic activity was crucial important for the accumulation of the royal power during such key periods as the late eleventh to early twelfth century and the early fourteen century.

In addition to strengthened financial power, the capabilities of the kings were no less important. Louis VI and Philip Augustus who had strong and effective personalities were able to tighten the ties or vassalage and re-affirm its hierarchical character. They were willing to take judicial and military action against the disloyal lords if needed. In contrast with kings and princes who were able to avoid the sub-division of their property by inheritance, lesser nobles were weakened by the passing of each generation. The weak nobles of the surrounding area were forced to do homage.

The Capetian kings

were also blessed by the church. The

doctrine of monarchical superiority was clearly enunciated by Louis VI’s

adviser, Suger, the Abbot of St. Dennis, who insisted that vassals of the king’s

vassals owed primary allegiance to the monarch, rather to their direct

seigneurs.[9] This ran contrary to the long

established custom that “the vassal of my vassal is not my vassal”, and Philip

Augustus was able to require homage from King John of

Marriage and dowries they brought were

another means by which the Capetian kings acquired

territory. Philip Augustus in 1180,

for example, obtained the Boulenois and

Immediate

Cause of Hundred Years War

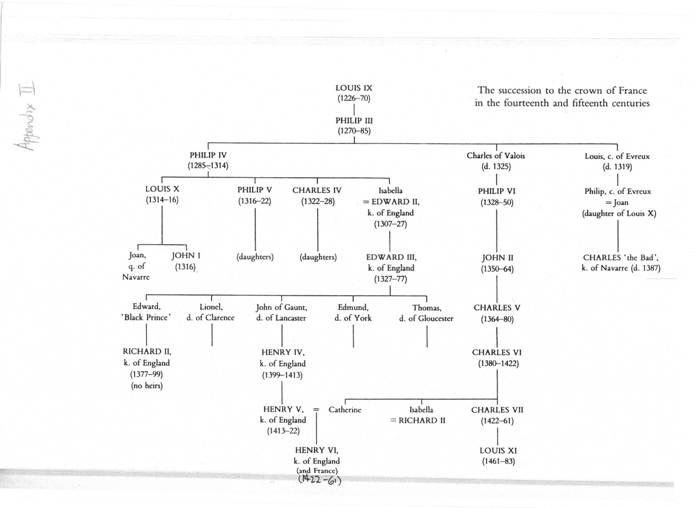

Charles IV had no direct heir as king of

Philip of Valois was recognized by an

assembly of leading nobles and clergy meeting at

The issues of

The

End of the Hundred Years War

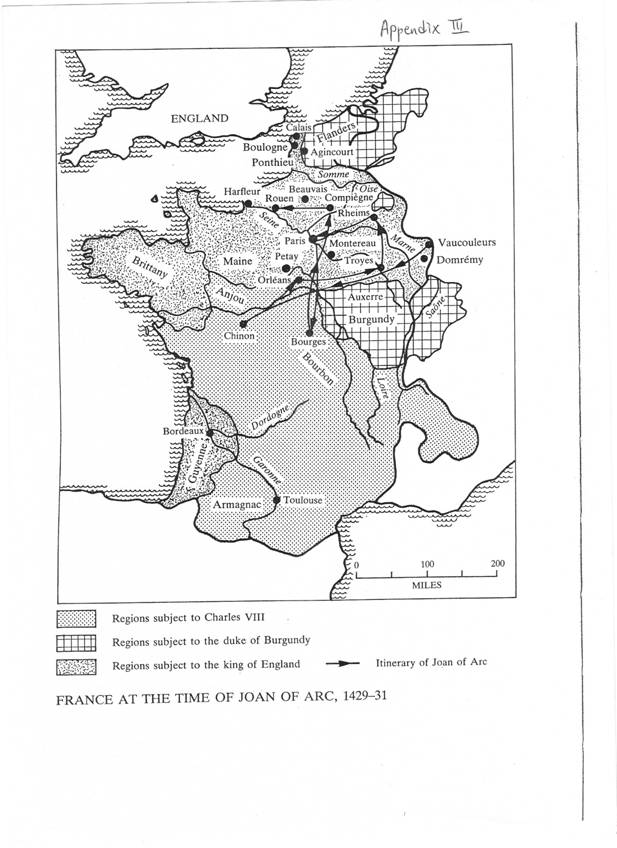

The roles of the Dukes of Burgundy in the

Hundred Years War had attracted less attention than it deserved. John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, had

long been the political rival of Charles VI. John the Fearless tried to create a

puppet government at

One of the most significant turning-points

was undoubtedly the appearance of Joan of Arc. She helped Charles VII to win several

battles and recover a significant portion of land, and be crowned at

Without the support of the Duke of Burgundy,

the effective governing of the land under English domain was impossible

considering that the manpower of the English troop was limited. The military resources of

Analysis

of the relationship between the feudal system and Hundred Years War

According to Max Weber, the property ownership and the control of violence are empirically closely related. In feudalism, militarized landlords, united by oaths of mutual responsibility, were organized to protect themselves and their property against external invasion and internal rebellions and uprisings. Alternatively, their protected wealth enabled them to employ professional warriors in their service.[11]

If we step into the medieval age, we would note that the contest for the throne could also be seen as the issue of succession of the estate of the royal family. When the succession rule is not clear enough and given that the estate was worth more than the harmony between the family members, a fight amongst the relevant parties could be anticipated.

Before the Capetian Dynasty, the throne was not highly sought after by the great nobles. The king performed nominal authority over his vassals. It can be noted that the king was selected amongst the great nobles through negotiation. Land ownership was far more important than the throne itself. Nevertheless, the throne was associated with the land under royal domain. The attractiveness of the throne came from the land instead of the throne itself.

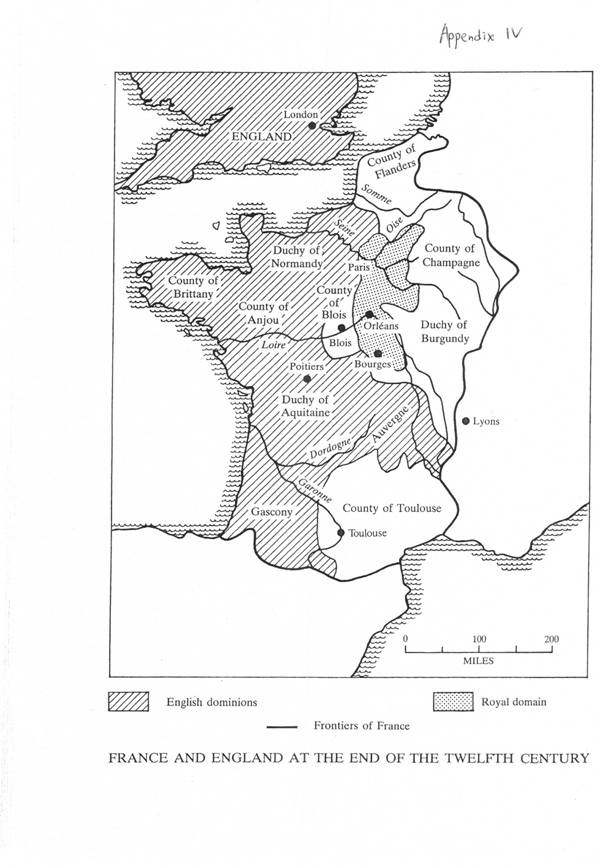

After the development of a few centuries, the royal power was strengthened through the prosperity of the region under or surrounding the royal domain, political marriage as well as the development of a centralized judicial institution as discussed above. Such development made the throne more attractive when Edward III laid a claim on it.

The triggering issue of the war was regarded

as the succession of the throne.

However, the seed of the war can be traced in the twelfth century Henry II

simultaneously became duke of

The industrial wealth of

Another area of disputes between king of

Furthermore, knights underwent years of training or even life long training. In order to become a lord or climb up in the military career, he had to take part in warfare and assisted his lord won the battles and hence occupied the lands of his rivals. This is the only means the knights can climb up the social hierarchy. If the knights lacked such channels to do so, the whole chain the social mobility would be broken. As discussed above, being a knight was a dangerous career. Yet it attracted many young people to do so. They were not afraid of being killed in war. They dreamed to be lords some day. Moreover, the nobles themselves were also trained to be knights. Once there was opportunity, they would like to demonstrate their skills which they were equipped with for so many years. Under such circumstances, both the nobles and his knights were keen for battles.

The chronicles described that warfare had

been aptly called the national industry of the

Conclusion

In the medieval age, land is the most

valuable asset amongst all the resources.

People would use every effort to have a parcel of land of their

own. When there was more than one

owner regarding a piece of land, it would create many problems. Every owner wanted to take advantage of

the activities over the land. If

one of the owners could prevail over the others by military power or other

means, the land could be rested in peace since the other owners had no choice

but followed the sole authority.

However, if there were two or more equally powered owners and when a

single owner tried to expand his interest at the expense of the others,

quarrels would happen and subsequently led to war. During the Hundred Years War, several occasions

of negotiations had been made but none could lead to a prolonged period of

peace. A practical issue was that

the settlement between the King of

Reference

Pierre Goubert, ‘The Course of French History’, Routledge (

Price, Roger,

“A Concise History of

Marjorie Chibhall, “The Normany”,

Blackwell Publisher,

Jonathan Sumption, “The Hundred Years War I, Trial By

Bryan S.

Turner, “For Weber Essays on the Society of Fate”, SAGE Publications Ltd,

張芝聯主編,法國通史,遼寧大學出版社,1999。